Sunshine Daydream

Saying goodbye to the Grateful Dead

(Regular readers of the Context Maker will know that I generally look forward to what’s coming next. This week, I’m looking back.)

Well love is love - and not fade away.

The first time I heard Bobby Weir sing live, it was a Buddy Holly tune that I knew best from its cover version by the Rolling Stones.

I was a hardcore Rolling Stones and Pink Floyd fan and had just discovered reggae when I moved to San Francisco from the UK at the age of 14. American Beauty was in my record collection and on my turntable from time to time, but it was not in heavy rotation. I was moving from an all boys boarding school in Britain for which the term ‘old school’ was insufficient - watch Lindsay Anderson’s If to get a flavour of what it was like - to a co-ed high school in Marin County where I learned a lot more about life than I did about maths.

San Francisco was a radiant city to me. At the end of that first summer, just as school started, I went to a free concert in Golden Gate Park - it was the first show by the newly minted reboot of Jefferson Airplane as Jefferson Starship. And it was also my first experience of the live Dead.

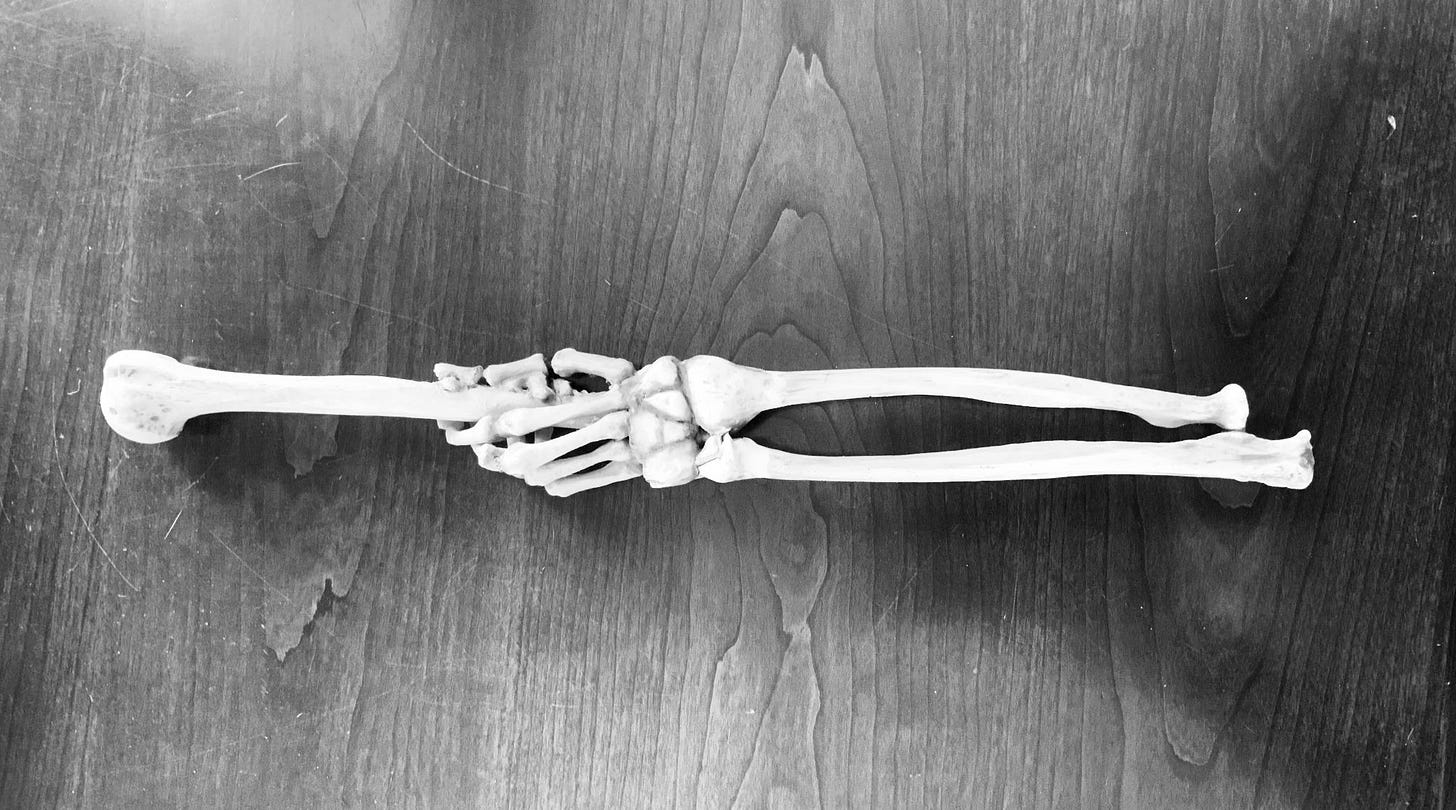

What is this, you ask? Some archeological relic of an ancient human tribe? A long ago warrior’s frozen death grip on an improvised weapon? Perhaps the missing link to the first violent ape inspired by the monolith in 2001?

In a way, it’s all of these, and none of them. Mostly, it’s a touchstone for me - to how I became who I am and what I hold on to over time. It’s Mickey Hart’s right arm and drumstick used for close-up shots in the Grateful Dead music video I produced for ‘Touch of Grey’. It lives on my bookshelf with other talismanic treasures from the past. Okay, I’ll admit it, over the years, it’s also served as a stand-in for a shank bone on our irreverent seder plate. But for me it symbolises a moment when things went wildly on and off the rails, some lessons learned, a time and a feeling that I never want to lose.

Like millions of others, I’m mourning the loss of Bob Weir. Deadheads have already been through a great deal of loss - most obviously of Jerry Garcia, but also of Pigpen, Keith and Donna Godchaux, Brett Mydland and Phil Lesh. Yet one way or another, the music has rolled on. Now the last remaining voice of the Dead has gone where the wind blows and it finally feels like a kind of end. Or at least the closing of a circle.

I have impressionistic and honestly somewhat cliched memories of that day in 1975 - wine skins and Zigzags, whirling dancers and rainbow streamers, a naked guy standing stock still, drooling impassively as the crowd flowed around him, that lilting and soaring Garcia guitar, and Bob Weir’s voice belting out the lyrics to ‘Truckin’. I remember Garcia singing ‘Franklin’s Tower’, a brand new song at the time, and went home with its hook in my head. You better roll away.

My real conversion to the Dead happened gradually though. Going to their shows became part of my new social life in the city. Winterland. The Cow Palace on New Year’s Eve. If the Dead were playing, the kids I was at school with were going. Later on, at the Greek Theatre in Berkeley. Frost down at Stanford. By the end of those years when I lived in the Bay Area, I’d seen the Dead play more than any other band by a wide margin. And their music was a gateway drug to other genres it grew from - for me, that was bluegrass, folk Americana, and jazz.

I moved to New York soon afterwards for university and Lou Reed’s dirty boulevards, Sid Vicious at Max’s, Patti Smith at the New Elgin, Talking Heads at the Loeb student centre. The Dead’s albums were in my collection, but played second fiddle to the Clash. Until I returned to San Francisco in the mid eighties and got a job at the animation and effects studio Colossal Pictures. One of Colossal’s founders, director Gary Gutierrez, had made the animation for the Grateful Dead movie, so it was natural for the Dead to approach him about making their first ever music video. The band had just signed a deal with a new record label, and the execs there were determined to make them a commercial success. I remember listening to their planned single repeatedly in Gary’s office, helping him develop video ideas for what would become the band’s only top ten hit. ‘Touch of Grey’.

Gary knew the band were reluctant to do a video at all. Abbey Konowitch, the Arista Records exec, was pushing them down this path. It’s hard to remember now that the Dead were really the originators of modern fandom - building an unmediated relationship with their fans through live musical performance and a community ethos. Shakedown Street was an actual place in Deadhead campsites, not an approach to fan monetisation. The Dead were reluctant to make something inauthentic and purely promotional. I remember Phil Lesh being particularly opposed to the entire undertaking.

The idea we came up with - to build life size skeleton caricatures of each member that would perform the song in the video instead of the band - was in part designed to convince the Dead that the video could be made without them having to perform in it themselves. But it also spoke to the core principles of the band - by filming the puppets live on stage with an audience of fans, we would be cementing that community connection.

In the end, Arista insisted that the band appear at the end of the video. Phil was convinced to participate. And we started planning the video for ‘Touch of Grey’.

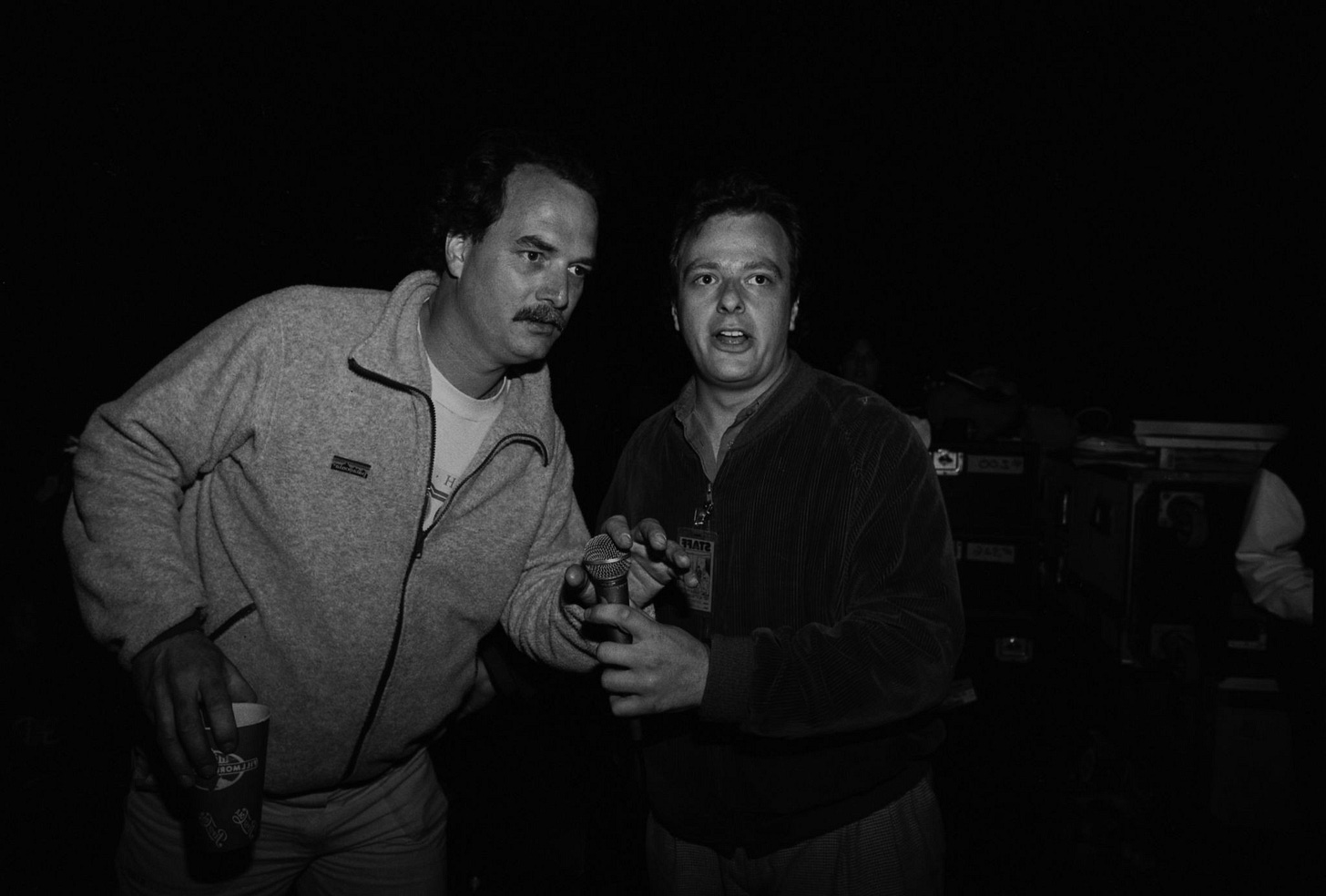

L to R: Me, Bob Weir, Abbey Konowitch, Jerry Garcia, Gary Gutierrez

Creative contributions from me were minor. Gary deserves all the creative credit, alongside director of photography Rick Fichter and the brilliant puppeteers led by Gary Platek. I was the producer, and my accomplishments were really on the logistical side. Imagine planning and wrangling a shoot at night in between two daytime shows at Laguna Seca Raceway with multiple camera crews, six life-sized skeleton puppets performing live, thousands of Deadheads in various stages of inebriation as extras, rigid visual effects requirements and one globally renowned rock n’ roll band notorious for quixotic improvisation.

Then throw in the probably predictable but still unexpected spiking of some crew members with LSD and the drop in temperature at Laguna Seca Raceway at night to unforeseen lows accompanied by thick ocean fog rolling in and you begin to get a fuller picture. As delays in our shooting schedule grew, Bill Graham, the doyen of west coast concert events, told me I needed to speak to the increasingly restless crowd we had summoned from their campsites back into the venue for the filming.

I’ve done a great deal of public speaking over the years, yet even now, I suffer occasional anxiety speaking to large groups, flashing back to that night. I hadn’t yet learned how to get the audience on your side - how to use humour and even vulnerability to connect with the crowd. The Deadheads hadn’t left their sleeping bags to hear from a young producer with a nervously polite British accent asking them to be patient. The yelling began.

“Dark Star”.

“Bring out the Dead”.

“Midnight set!”

The chants and even some boos grew louder, drowning me out as I asked them to sit and wait. But what was this? Suddenly, they were cheering! Bill Kreutzmann, one of the band’s two drummers, had come to my rescue.

This moment was captured in all its humiliating detail by photographer Jerry Spagnoli.

”I say, would you mind sitting down for a bit?”

Like a deer in the headlights. I’m rescued by Bill Kreutzmann (who may or may not have had a few beers).

Bill employs the sensible strategy of making fun of me as I continue to stress…

… then brings me in on the joke.

Confidence restored, I’m finally able to explain what we are trying to accomplish to the crowd.

Bill brought me into the Dead family at that moment, rescued me, and connected me to the band with lessons I remember every time I step on a stage. The crowd were amazing, and you can see in the final video that they brought the same joy in response to the puppets as they would have if the band themselves were performing.

The wider Colossal studio family was there too - it seemed like half the staff had volunteered for a role on the production so they could be part of the experience. The brilliant animation director George Evelyn somehow wound up late in the evening handling the clapper board used to synchronise sound with picture at the start of each take. Mighty as he was at wielding a pencil, George struggled with this simple task . To be fair, it was made more complicated by the need for the clapper board to be visible to all camera crews around the venue. By this point, the band were on stage, and George was positioned directly in front of Jerry Garcia. The assistant director kept yelling at poor George to keep the clapper board at the right angle. Soon, the crowd picked up on George’s struggles. “Come on, George”. “Get it together, George!” The more they yelled, the more flustered George became. Finally, Jerry leaned over to him and paraphrased the song we were there to film, whispering: “It’s alright, George. You will survive”.

Everyone’s laughing now - apparently I’m the only one who’s noticed a loose stage light is precariously close to falling on us.

We all survived, somehow.

Keyboardist Brett Mydland shows us the chords he plays at the moment in the song we plan to transition from the skeletons to the live band.

Gary and I went to screen the completed video for the band at their rehearsal space in San Rafael. They were preparing for a new tour with Bob Dylan, who wandered into the room with Bob Weir as everyone assembled for the screening. Squatting to the side, Dylan squinted at the screen. About thirty seconds after the video started, he put on a pair of sunglasses. About half way through, he got up and went into the bathroom, from which he never emerged.

Fortunately, the band were delighted. ‘Touch of Grey’ was all over MTV in days, and became the band’s bridge to a whole new audience.

In an age of digital magic, the video looks hand crafted, but even then, this was a deliberate choice. We wanted the viewer to see the strings and feel the genuine response of the crowd. Even if you were making the video today, with our massive arsenal of VFX and AI at hand, you’d still want to do something as crazy as puppeteering life size skeletons in live performance in front of real fans in the middle of the night - because that kind of daring improvisational authenticity and link to their fans was what the Grateful Dead were all about. Some experiences lose their meaning when they’re overly polished and buffed. Sometimes tech should just stay in the tool box.

The last time I saw the Dead live was at Frost in the early nineties - what I ate beforehand I can’t remember but I do know the band played ‘Dark Star’ that day. And that I was literally on stage behind the huge gong for part of the show, watching the performance up close. And the many flecks of sweat off Mickey Hart’s brow during his drum solo were flying prismatic through stagelight like escaping sprites.

That was over thirty years ago. I’ve listened to the Dead’s music pretty much everyday since. I’m listening as I write this. Now I’m the one with a touch of grey.

It’s mid winter and another storm is lashing the south coast of England. Mickey’s skeletal arm is back up on the bookshelf. I’m looking out at the beach in the wind and rain. But in my mind’s eye, I’m back in that tie-died, stir-fried San Francisco field the very first time I saw the Dead for free. Sunshine daydream.

All backstage photos by Jerry Spagnoli. I can’t resist ending on this image he took of Cathy, my own sunshine daydream, looking gorgeously cool as ever in front of the Dead’s double drum kit set-up on stage.

A lovely recounting, thank you. I, too, was beholden to The Clash before becoming a deadhead. Still have my stub from Bonds (along with 77 Grateful Dead ticket remnants).

Great story, Japhet, and well told. Those were good times at (C)P.